Acoustic Guitar: A Private Lesson With Steve Gillette

Steve with Orville Johnson (center, author of this article)

and Scott Nygaard (left) at the Puget Sound Guitar Workshop |

This article appeared in Acoustic Guitar Magazine, in the August 2007 issue (No. 176). Article is reprinted here by permission of Acoustic Guitar. Updates to latest recordings and equipment are noted immediately below the original text.

By Orville Johnson

The renowned guitarist and songwriter talks about the

influence of Clarence White, his father's stride piano, and his own banjo

playing on his hybrid style of flatpicking. With audio examples.

AUDIO: Tune Up AUDIO: Tune Up

Steve Gillette is well known among songwriters, having written one of the best

books on the subject (Songwriting and the Creative Process; Sing Out!

Publications, 1995); had his songs covered by the likes of Garth Brooks, John

Denver, Linda Ronstadt, and many others; and penned a tune that has become a

standard of the modern folk repertoire, "Darcy Farrow"—a song so classic in its

architecture that many people incorrectly assume it's traditional. He has also

written songs for films (and for Disney characters Winnie the Pooh, Jiminy

Cricket, and Dumbo) and received honors from ASCAP and BMI. He has an

instructional CD on his guitar style, and his latest CD is Being There (www.stevegillette.com).

Update (2013): Later recordings: The Man (2010), and with Cindy Mangsen, Home By Dark (2012) and Berrymania (2013).

Overshadowed by his writing achievements is a unique guitar style that

developed from hearing his father play stride piano, meeting flatpicking icon

Clarence White in 1960, and playing bluegrass banjo as a teenager. Somehow he

swirled all these elements into a way of playing that uses the flatpick and two

fingers to careen back and forth between pattern picking, muted rhythmic

strums, picked melodic lines, and enough contrapuntal moving voices to make you

wonder how many guitars are actually playing. We got together before a gig

earlier this year in San Luis Obispo, California, and talked about his style.

How did you get started with this technique?

Bluegrass was very close to the center of things I was drawn to. I met Clarence

White in 1960 when I was at UCLA. He and his family had just moved out west.

They played at the Ash Grove and I took part in the Sunday afternoon folk-music

contests they had there. My bluegrass band had formed at UCLA, and I was

playing banjo at that time, but I was really drawn to Clarence White's playing,

not only because of his expertise but also because the tone of it was so

wonderful. So I realized how much you could do with a flatpick.

Did the idea of combining the pick and fingers in this manner have

something to do with your banjo playing?

The whole idea of patterns was part of that. Also, my dad, who is 85,

played — and still plays — stride piano. As a kid, I heard him playing with the strong rhythmic thing, that stride left hand. It's not just a boom-cha boom-cha; it's a swing, a built-in syncopation. I think that accounts for some of the rhythmic emphasis I get.

Explain the basics of what you're doing with your approach.

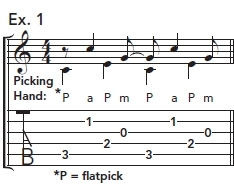

A lot of it comes from Merle Travis's style. He would play it with a thumbpick

and one finger. I use two fingers—middle and ring—while holding the flatpick

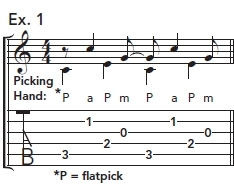

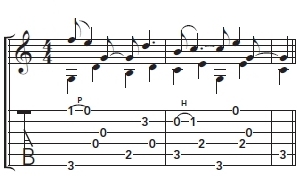

with my thumb and index. One pattern I use a lot is pick-ring-pick-middle [Example 1]

AUDIO:

Example

1. AUDIO:

Example

1.

I

tell people to take the inside four strings of a first-position C chord and

play that pattern: outside, inside, ring, middle. Then the next variation would

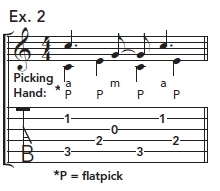

add a pinch [Example 2]  AUDIO:

Example

2. AUDIO:

Example

2.

If

you're gonna pinch on the downbeat, you won't have a finger available to play

the next eighth note, so you leave out that eighth note and play the next thumb

(flatpick) beat, then leave out the last eighth note because you're getting

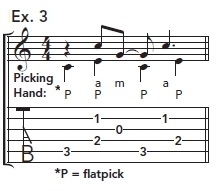

ready for the next thumb beat. The next variation would be putting your pinch

on the off beat [Example 3].

AUDIO:

Example

3. AUDIO:

Example

3.

To

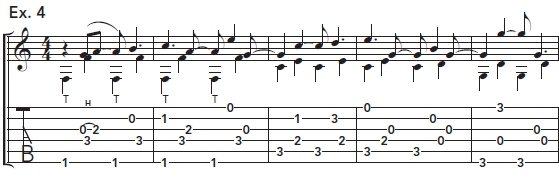

combine them all, you start with the four-beat roll, then go to the pinch on

the offbeat, maybe back to the roll, and a measure of pinching on the downbeat.

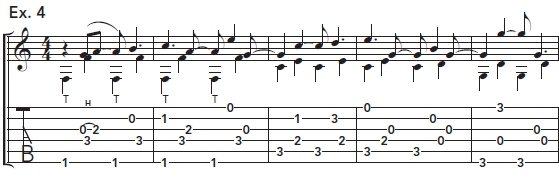

Then you add some melody notes with some hammers or pull-offs [Example 4].

AUDIO:

Example

4. AUDIO:

Example

4.

Pinching

on the downbeat means grabbing strings five and two, and the offbeat pinch is

grabbing four and two, so the bass is really alternating between five and four

and the fingers between two and three. Eventually, of course, you move on from

there and add some complexity in the melodies.

Different keys give you different things, too. The "Darcy Farrow" thing all

comes out of the D position, the first inversion up the neck of D. It's in

dropped-D tuning. That's really where the song came from, 'cause I was

exploring that back in 1965. I came up with the guitar part, and my friend Tom

Campbell came up with the story. We worked on it quite a bit and drew on the

Scottish-Irish ballad tradition. I wanted it to flow in a music-box sort of

way.

Update (2013): Darcy Farrow was written in 1964, not 1965. The Darcy Farrow examples are better explained in two instructional videos Steve prepared. You can find them on this site on the Steve Gillette and Cindy Mangsen You Tube Videos web page.

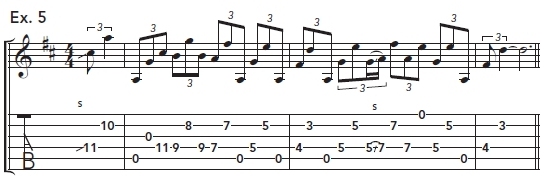

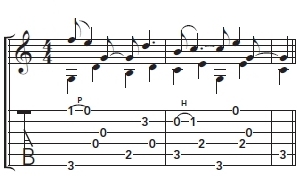

I noticed you use a lot of this style in your version of "Corrina."

I'm using a lot of two-string harmonies on strings two and four—the parallel

sixths, inverted thirds—and ringing an open string on the bottom [Example 5].

AUDIO:

Example

5. AUDIO:

Example

5.

I learned this from Bruce Langhorne. What I like about this particular piece is

exploring the area of open voicings. So you're really only hearing three notes

at a time, but some sustain longer, like the bass note under the high notes. I

love to listen for the resonance of the bass.

Thinking

about Eddie Lang and those guys, I think one thing they discovered was that the

charts for the big bands had the voicings extended out for the horns—the 9ths

and 11ths and so forth—but the guitars couldn't play all that. So they had to

use inverted versions but boil it down to three or four notes. The great thing

about that is that it gets to the center, the "heart chakra" of the tune.

You're trying to get different densities, different energies with just one

guitar. LICK OF THE MONTH

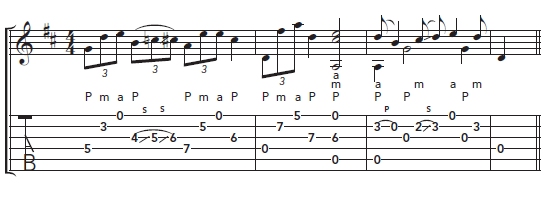

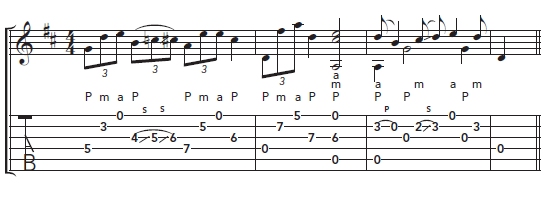

This catchy riff closes each verse of Gillette's poplular song, "Darcy

Farrow." Give each triplet note its correct value (you need to hear all

the triplets) to get his music-box lilt.

[Lick of the Month]

AUDIO:

Lick of the Month. AUDIO:

Lick of the Month.

INSTRUCTION

Steve Gillette's Equipment PicksWhat he plays.

By Orville Johnson

|

|

|

•Guitars:

Modified 1990 Alvarez Yairi DY61 cedar top. "I had been playing with my

guitar tuned down a half step and then capoed up but finally moved the nut to

get to my current setup," Gillette says. "This guitar is the closest I've

come to the right feel for me: shorter scale and string length. I had the nut

moved up one fret, so it's now 13 frets to the body. I still use medium

strings, so there's no loss of tone, and I also spent the extra $100 and

moved the dots so I don't get lost."

Update (2013): Steve now plays a 2010 Martin OM-21 with John Pearse light guage strings. Steve Sauve in North Adams, MA, set it up with a compensated saddle and installed the k&k Pure Mini transducers.

•Picks: Dunlop .88, with grip.

•Strings: John Pearse 600L mediums.

•Mics: Shure SM81 (guitar); AKG 535 (vocal).

•Pickups: L.R. Baggs iBeam.

•Effects: DigiTech RPx400 chorus/reverb.

|

|

![]()